Reference:

dynamic programming

Those who cannot remember the past are doomed to repeat it. — George Santayana

Recursive algorithm has the downside of repeating the same calculation but with dynamic programming and some clever recursion, it can be a very powerful method for solving certain problems.

The key to make the recursion work is to get insight into the substructure properties of the problem. This is often the hardest part of using dynamic programming and not just filling tables.

palindrome

A subsequence is palindromic if it is the same whether read left to right or right to left. For example, the sequence

A, C, G, T, G, T, C, A, A, A, A, T, C, G

has many palindromic subsequences, including A, C, G, C, A and A, A, A, A.

note a palindrome substring is similar but it must also be a contiguous sequence.

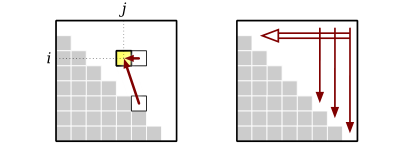

In this example, we use two \(n \times n\) tables to keep track of the palindrome length array and the optimal path bt.

Basis: (1) Any character is a palindrome of length 1. (2). Any two equal and contiguous sequence is a palindrome of length 2, if not equal (3), it is considered as palindrome of length 1.

for i in range(1,n-1):

array[i][i]=1

j = i + 1

if A[i] == A[j]:

array[i][j] = 2

bt[i][j] = '/'

else:

array[i][j] = 1

bt[i][j] = '|'

array[n][n] = 1In this case, '/' is used to mark the index of the optimal path and '-' and '|' are marks for traversing horizontally or vertically through the bt table.

During recursion, as the two index i and j moves outward, the palindrome increase by 2 if (4) these two new sequences are equal. If not equal, the palindrome does not increase and (5) it is the maximum of the recursion before it.

Once the table is complete, the complete path can be traced by printing the characters at the index marked. In this example, the longest palindrome is: GCAAAACG. Also, note that the space complexity is \(O(n^2)\) for using 2 \(n \times n\) tables and the running time is also \(O(n^2)\) to fill each cells.

coin change

There are a few different ways for solving the coin change problem. The easiest one is perhaps greedy algorithm but it does not always give the optimum solution if the coin values are not power of each other. Let \(A = 29 \) and the coin values are \( V = [1,3,7,12]\).

Basis: (1) The change is 0 for value \(v=0\) and (2) the change is 1 if v is equal to the coin denominator.

Recursive: the optimum solution is the one that return with the minimum number of coins after each subtraction \(v - V_i\).

$$T[v] = \min_{V[i] \leq v} \big(T\big[v-V[i]\big] + 1 \big)$$

The table should be an array of length \(n = A+1\) to track all the optimum solution for values \(v\) less than \(A\) and for each cell, it tracks the optimum solution array \(C\) of length \( m = length(V)\) and integer \(sum\) for that array.

def coinchange(coins, A):

T =[ ([], float('inf') ) for i in range(A+1)]

T[0] = ([0 for i in coins], 0) # basis

c = [ 0 for i in range(len(coins))]

c,s=helper(coins, A, T, c) # recursive helper

return c, sIn this example, the most optimum solution is \( C = [2, 1, 0, 2] \) with \(sum = 5 \). The space is the \( O(mn) \) table and the run time is also \(O(mn)\) for each value \(v\) less than \(A\) and each coin denominator \(V_i\).